Transnational and Planetary Threats – Variable 5: Climate, Peace, and Security

Variable 5: Climate, Peace, and Security

Climate change is a vast and complex issue that permeates virtually every aspect of human society, including international politics. It is among the most urgent tasks humanity confronts in our era. A comprehensive response to climate change must aim for profound and transformative reform of global political, economic, social, and normative spaces. It must address mitigation, adaptation, technology, finance, and our ideas of consumption and equality.

Due to the Better Order Project’s security focus and internal expertise, this report is centered on how climate change will affect international security and, in that context, which substantive policy approaches are achievable and practical.

However, this focus and the proposals below by no means negate our view that the international community must address all dimensions of the climate question if we are to achieve a better and more sustainably prosperous world. These include the importance of climate change as a matter of collective responsibility with the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities principle at its core.1 The distressing reality is that the Paris Agreement commitments on climate finance, technology transfer, and emission reductions remain far from being met. These failures have increased the likelihood of greater warming and its potential security impacts.

The term “climate security” traditionally covers the linkages between climate and conflict. However, many have also expanded the definition to include human security. While this report does address human security, the focus is mostly on risks of conflict and existential threats to states.

Climate security is a contentious area in the global order, as U.N. Security Council debates have revealed.2 A key resolution on the topic failed at the Security Council in 2021, with Russia and India voting against it and China abstaining.3

The European Union tends to lead in the push for securitizing climate change, with the United States supporting or opposing this approach depending on the party in power in Washington. Russia and China have historically opposed or been skeptical of a “climate security” framework, as have India and more than 80 Global South states. Opponents most often object to securitization because they see climate change as being related predominantly to development — they wish to maintain the centrality of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), question links between climate and conflict, and worry that Western states might use climate change as a pretext for Responsibility to Protect–type coerced interventions.4 However, other Global South states, such as SIDS countries and highly vulnerable states, have mostly supported the securitization of climate change and its appropriateness at the U.N. Security Council.

Research on climate security is evolving, but it is clear that climate change and security are linked in highly complex ways. There is no simplistic causation between intensifying climate change and greater conflict. But climate change impacts security (and vice versa) through critical intervening variables such as preexisting social cohesion, state capacity, and regional dynamics, which are crucial in the impacts of climate-magnified factors such as resource scarcity, mass migration, and natural disasters.5

Going forward, major divides may persist on finance, technology transfer, and the phasing out of fossil fuels, with some wealthier states and oil producers likely to be the most recalcitrant. However, as the global mean temperature continues to rise and climate-related disasters multiply, there is likely to be growing worldwide acceptance of the links between climate and security, even if some states remain wary of over-securitizing the issue. This may lead all sides to accept the necessity of compromise and collaboration on the most urgent aspects of this nexus.

The following proposals envision substantial yet achievable advances in tackling climate, peace, and security.

Proposal 13: Bridging the global divide on climate security

This proposal charts a new path that resolves the United Nations’ climate security divide.

Halt attempts to pass a U.N. Security Council resolution on the topic, noting the deadlock on the climate security question at the UNSC and the fundamental divides that characterize the debate.

Adopt a new U.N. General Assembly resolution with the following elements, noting that the GA already has a history of taking on the broader topic of climate change, including a recent request for an advisory opinion from the ICJ and defining access to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a universal human right:6

- Affirm the centrality of the UNFCCC in international climate negotiations and that the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities should remain the basis of such negotiations. Reaffirm the goals of the Paris Agreement and subsequent international climate agreements.

- Recognize that scientific evidence points to complex and contingent linkages between climate and security. Intervening variables such as institutions and social cohesion play a critical role.

- Emphasize that meeting international commitments on finance, technology transfer, and decarbonization is the best way to avoid negative climate security outcomes and that a much greater focus on adaptation is a critical part of this effort.

- Reject any external military intervention in the internal affairs of states using climate change or climate security as a justification.

Proposal 14: A solutions-oriented “P20”

We propose the creation of a new informal grouping, the Planetary 20 (P20), to focus on climate security while balancing efficacy and higher ambition. It may also take on other issues in the climate area while retaining a focus on climate security.

This proposal recognizes the UNFCCC as the core negotiating forum but enables speedier action by a subset of states on climate security with the P20, convened under U.N. auspices. Just as the G20 transformed into a leaders’ summit during the global financial crisis of 2008, the P20 will be a leaders-driven body with an annual summit commensurate with the existential nature of the climate crisis. The grouping aims for deep engagement, consensus building, and coordination in an informal format, leading to problem-solving rather than formations of divisive blocs or “clubs.”

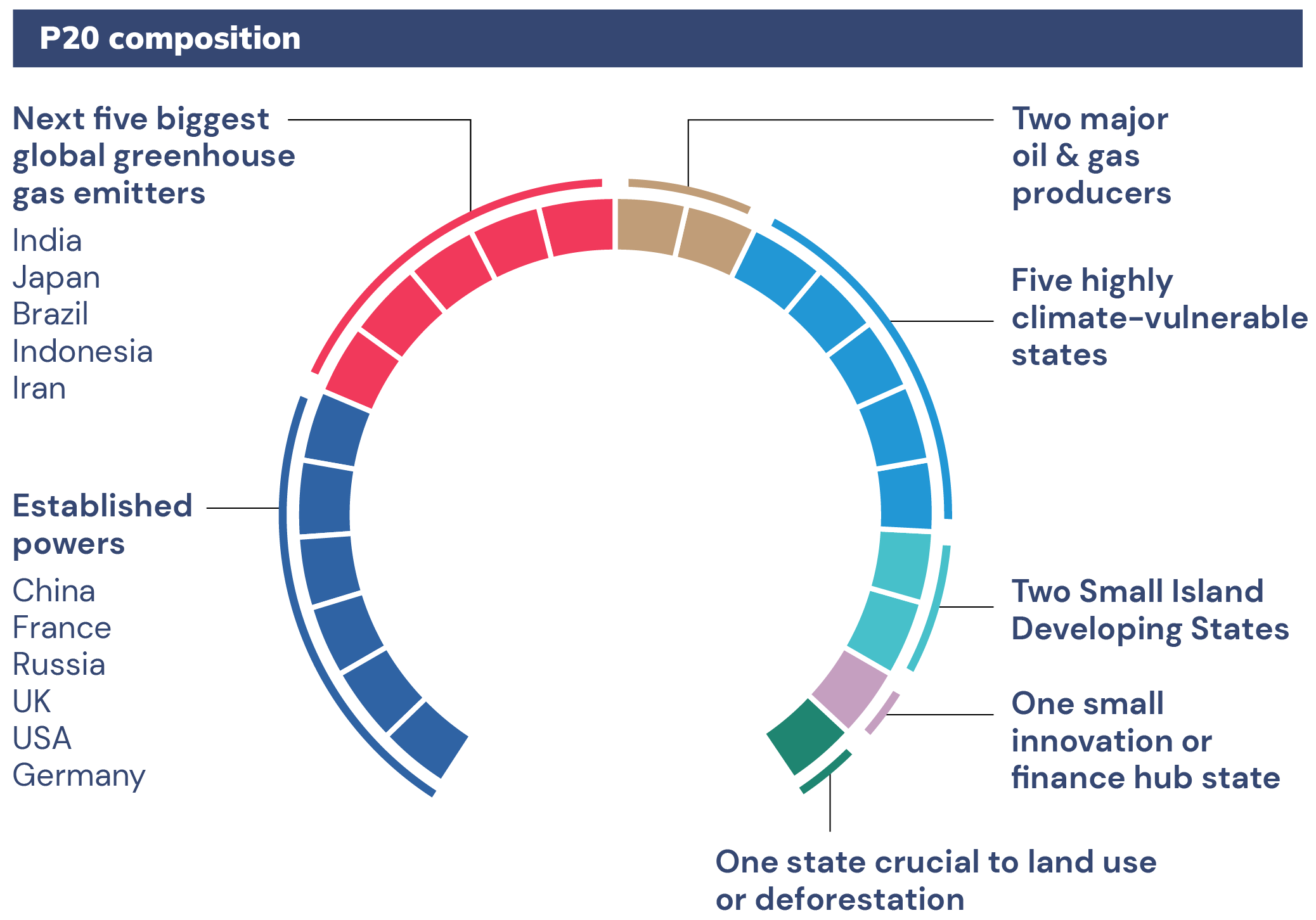

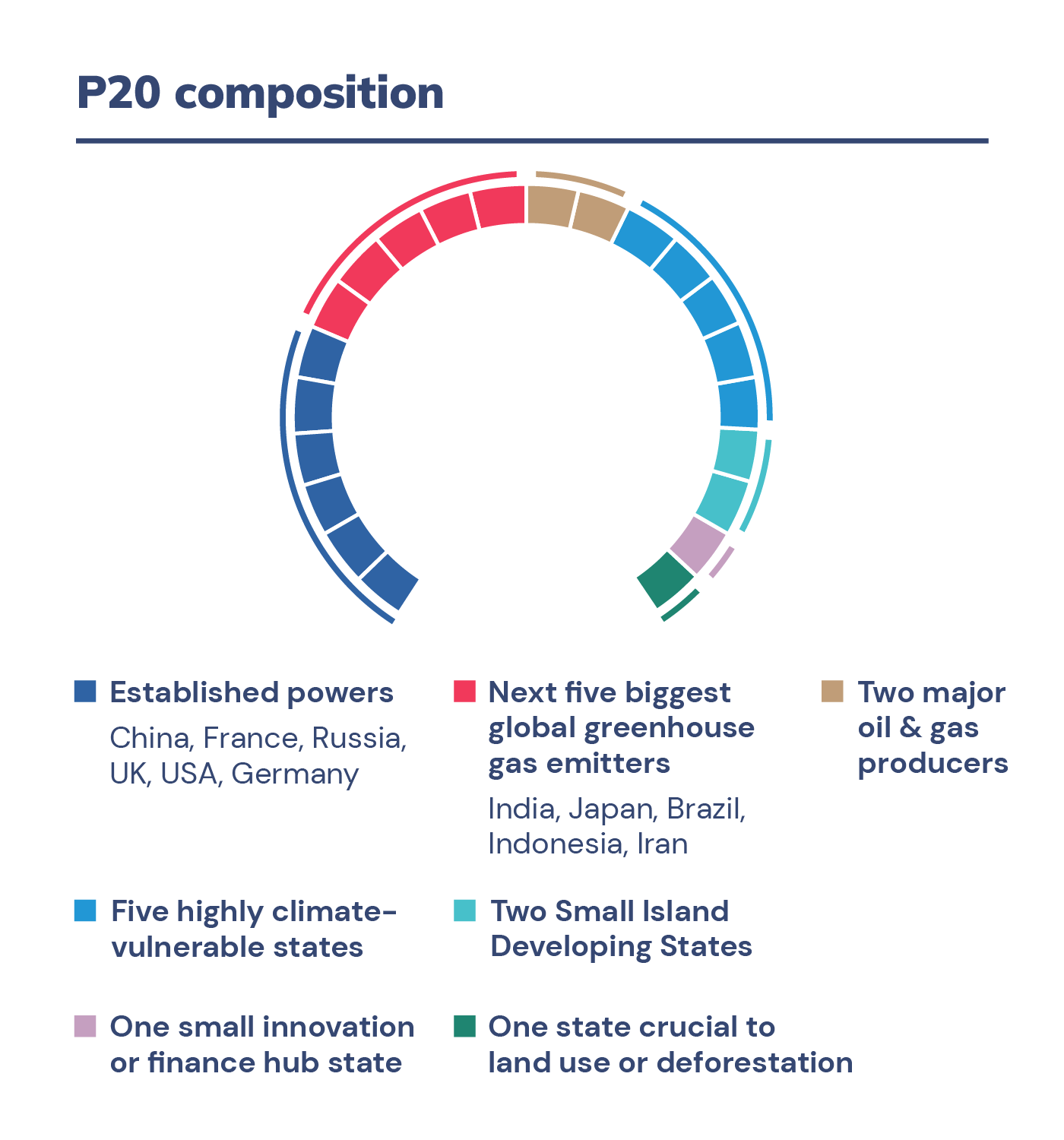

The composition of this new body must reflect the states that are most critical to solving the challenge of climate change while also being inclusive. Thus, the P20 must include great and middle powers, major historical and current emitters, vulnerable states, innovation hubs, and small island states.

The P20 should include the following sets of states:

- The five current permanent members of the U.N. Security Council

- Germany, as the host of the UNFCCC, and being, historically and currently, a major climate and renewables player from the Global North

- The five biggest global greenhouse gas emitters not included in (a), currently India, Japan, Brazil, Indonesia, and Iran

- Two major oil and gas producers that are not included in any other category (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Canada, Iraq, Algeria, and others)

- Five highly climate-vulnerable states to be selected from and by the existing Vulnerable 20 (V20) grouping of such states

- Two Small Island Developing States that are not included in any other category;

- One small state that is an innovation or finance hub and not included in any other category (e.g., The United Arab Emirates and Singapore)

- One state critical to land use or deforestation that is not included in any other category (e.g., Democratic Republic of Congo)

- Under no circumstances should the body have fewer than two members each from Africa and Latin America.

- If the body is to discuss a specific state or regional body, it should ensure that this state or regional body is invited and participates in these deliberations.

The P20 will be an informal body similar to the current G20 (i.e., without a permanent secretariat and staff), governed each year by a troika of the presidencies of the current, past, and next year. Such a structure has the advantages of a collegial give-and-take and may be less vulnerable to domestic politics. It is designed to be the first stop for problem-solving on climate, peace, and security, with its informal structure as a major advantage for achieving needed compromises. If and when the informal agreements and understandings it reaches on a specific problem gain wider consensus, long-term commitment, and are ready to be formalized (a desirable outcome), the U.N. Peacebuilding Commission (see Proposal 2 on U.N. Security Council Reform) and, ultimately, the U.N. General Assembly would be the logical bodies for this to take place.

Proposal 15: A new compact for Small Island Developing States

This proposal addresses perhaps the most existential climate security issue — the near-uninhabitability or disappearance of entire states and the consequent displacement of their citizens, unquestionably relevant to Small Island Developing States (SIDS). This group comprises 39 states with a total population of 68 million, with about 30 percent living at altitudes less than five meters above sea level. (This proposal does not address the issue of potential major migration from larger states, largely due to the major scientific uncertainties over the extent, geographies, and timelines of such migration and the low likelihood of achievable consensus among key states in the near future — a key factor for formulating proposals for this project.)

The 1951 Refugee Convention does not apply to environment or climate-displaced persons. There are non-binding declarations and regional conventions, such as the Cartagena (1984) and Brazil (2014) Declarations. The latter opens the door for the recognition of climate-displaced persons as entitled to protection. However, these regional initiatives do not represent a global consensus or norm.

Climate-displaced persons — the large majority of whom thus far have migrated domestically — are not, in and of themselves, a threat. However, the international community must prepare for undesirable scenarios related to climate change, which poses the clearest existential threat to SIDS.

Accordingly, the international community should pioneer a global compact within the next 10–15 years on long-term “climate visas” for the resettlement of some SIDS residents, to be operationalized in a phased manner in the second half of this century. The focus should be on residents of SIDS that have also been classified as the Least Developed Countries by the U.N. These are currently Comoros, Guinea–Bissau, Haiti, Kiribati, São Tomé and Príncipe, Solomon Islands, Timor–Leste, and Tuvalu.

- The granting of such visas should not be linked to extraneous conditions, such as concessions by these states on prohibiting or enabling military partnerships, alliances, access agreements, or basing rights as a part of regional or great power rivalries. Nor should it entail states giving up economic rights, including sovereignty over their exclusive economic zones (EEZs).

- For SIDS that could completely disappear by the end of this century, their EEZ revenue must remain accessible to their citizens and their descendants through an international agreement facilitated by the P20. International law is still evolving on questions such as how to administer revenue from these EEZs and how these states might continue to retain international personality through continuing citizenship of their climate-displaced citizens. The International Law Commission is engaged in developing detailed proposals on this topic. The P20, with the affected states invited, could serve as a venue for addressing these questions from a political standpoint.

Proposal 16: Strengthening regional leadership

This proposal aims to strike a balance between two constraints. The first is the strong opposition within wealthy states to major transfers of wealth to the Global South and the lack of leverage by the latter to achieve this goal. The second is the urgent need for the most climate-vulnerable states to preserve core aspects of their viability and security, for which a certain level of external financial support is essential. The proposal resolves this tension by identifying lower-cost approaches that still significantly strengthen climate resilience in the most vulnerable regions of the world.7

Recognizing that climate’s impacts on human security — and potentially on state stability — transcend borders, the P20 should propose a special allocation to an existing climate fund or channel (beyond the finances already committed through the New Collective Quantified Goal currently on the Conference of the Parties agenda). This additional funding should be dedicated to empowering vital regional organizations in the most climate-vulnerable regions and aimed toward strengthening and capacity building in activities such as installing early warning systems and providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.8 The principle would be for regional bodies to increasingly take the lead on climate security challenges — a version of “collective responsibility.” These organizations include, but are not limited to, BIMSTEC (South/Southeast Asia), CARICOM (the Caribbean), ECOWAS (West Africa), IGAD (East Africa), PIF (the Pacific), and SICA (Central America). The new Middle Eastern regional security organization proposed in this report should assume responsibility for addressing climate security in the Middle East and North Africa region.

The allocation should increase the funding levels for these organizations tenfold or more. Current annual budgets are typically in the low hundreds of millions of dollars for many of these organizations, so the required total expenditure for a quantum leap in their capacities would likely be in the range of $15 billion to $20 billion USD annually.

Funding should be principally furnished by the states in the Global North and China, though Global South middle powers with capability should also be encouraged to contribute. The international community should also explore additional innovative global sources of financing. The appropriate fund to house and disburse this contribution can be decided in due course. Still, the Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund, Loss and Damage Fund, and regional multilateral banks (such as the Inter–American Development Bank) might be the strongest candidates.

- The principle, enshrined in the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, notes that

all states should work to solve the climate change problem, but their responsibility to do so

is not equal. Rather this responsibility is differentiated — i.e., dependent on their respective

contributions to creating the problem, capabilities they can bring to bear, and their social and

economic conditions. ↩︎ - United Nations, “Security Council Open Debate on Climate and Security,” U.N. Climate Action,

Sept. 23, 2021, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/security-council-open-debate-climate-and-security-0. ↩︎ - United Nations, S/2021/990, U.N. Security Council, Dec. 13, 2021, https://

www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2021_990.pdf. ↩︎ - Sarang Shidore, “Climate Change Resolution Fails to Pass UN Security Council,” The

National Interest, Jan. 6, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/climate-change-

resolution-fails-pass-un-security-council-199105. ↩︎ - Joshua W. Busby, States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108957922. ↩︎ - United Nations, “The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy, and Sustainable Environment:

Draft Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly,” A/RES/76/300, July 26, 2022, https://

digitallibrary.un.org/record/3983329. ↩︎ - The recommendations in this proposal should not detract from the more significant efforts

needed to achieve international goals and commitments on climate finance, which are critical

to overcoming the climate crisis. ↩︎ - We assume that the U.N. system and international financial institutions will adopt the

Multidimensional Vulnerability Index rather than per capita gross domestic product for

assessing lending and development assistance needs. ↩︎