Variable 1: U.N. Security Council Reform

The proposals in this variable were updated in August 2025 following extensive consultations and engagement with government officials across all five U.N. regional groupings.

Based on current trends, relations among the P5 risk moving from dysfunction to total paralysis over the coming years. Besides their opposing interests in the realm of high-level geopolitics, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) may prove consistently unable to adopt resolutions on issues such as peacekeeping, sanctions, and punishment for war crimes. Cardinal norms of international peace and security (e.g., sovereignty, territorial integrity, and respect for international law) appear likely to remain subject to contested interpretations, even if they continue to enjoy nominal support.

The world is currently witnessing the proliferation of armed conflicts, a descent into great power competition, and mounting violations of international norms. Under these conditions, prospects for a universal order based on shared principles of global governance will become increasingly remote. And as mutual recriminations mount, there is a growing sense that the international order is reaching a tipping point.

Established powers have an interest in preserving the Security Council, given the avenues of influence it provides them.

Yet despite the sharp — and seemingly sharpening — differences exhibited in today’s international community, we must not forget the extent to which states still hold shared interests when it comes to preserving multilateralism and the role of the U.N. Security Council. Established powers have an interest in preserving the Security Council, given the avenues of influence it provides them. For their part, rising powers adamantly demand Security Council reform but still prefer it to be preserved as a forum for advancing their interests and mitigating conflict rather than have it drift into irrelevance. But structural and working methods reforms are urgently needed if the United Nations is to preserve its status as the premier forum for upholding international peace and security.

To that end, at the opening of the 82nd session of the U.N. General Assembly in 2027, after a consolidated model for reform has been presented in the Intergovernmental Negotiations (IGN) framework and text-based negotiations have begun, U.N. member states should vote to initiate a review of the U.N. Charter. According to Article 109 of the Charter, the decision to hold such a review can be taken with the support of two-thirds of General Assembly members and any nine Security Council members and is not subject to a veto.

Both the drafting process and the adopted text of the Pact for the Future have made clear that reforming the Security Council remains a priority for member states. The proposals outlined below carry forward several priorities identified during negotiations over the draft, including improving the representation of Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, and especially Africa; enlarging the Council in a fashion that improves the representation of small- and medium-sized states; finding an agreement on the question of the categories of membership; balancing representativeness and effectiveness; limiting the scope and use of the veto; and including a review clause to ensure that the Security Council remains fit for purpose over time.

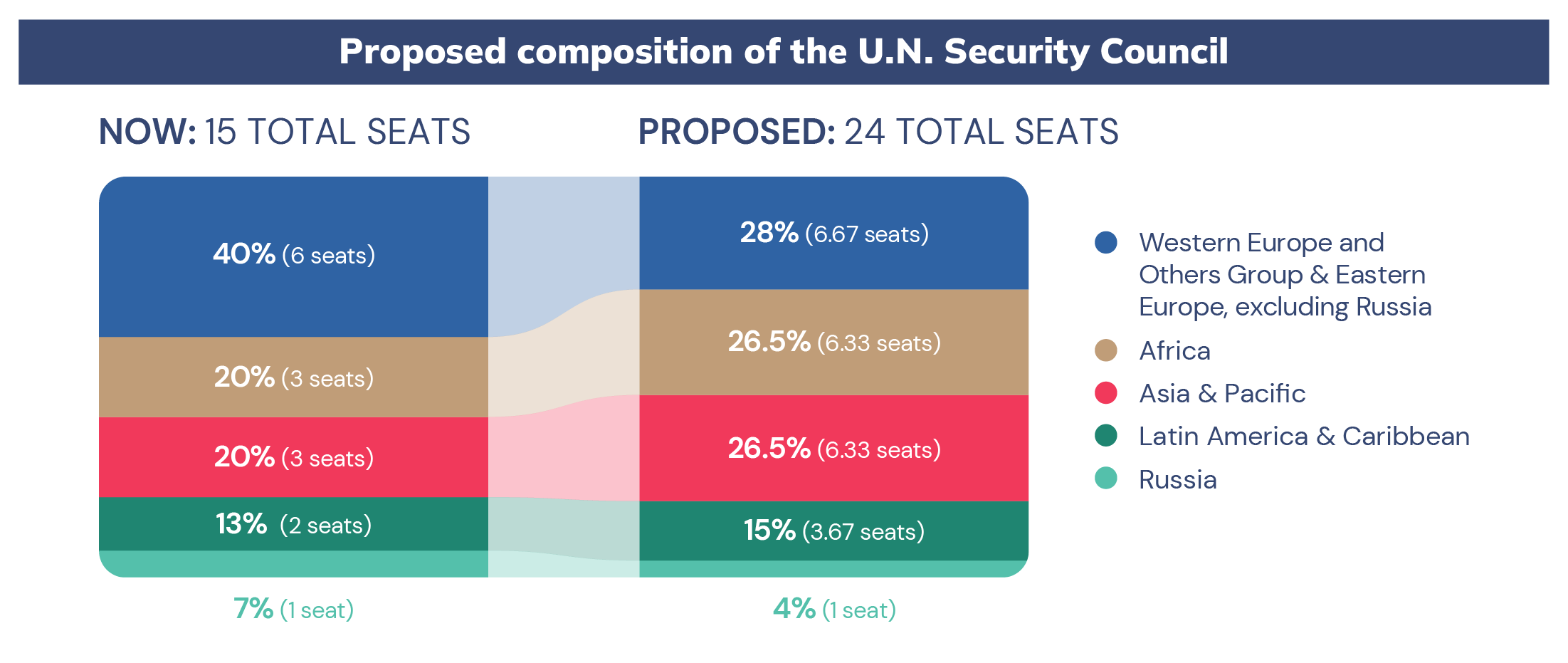

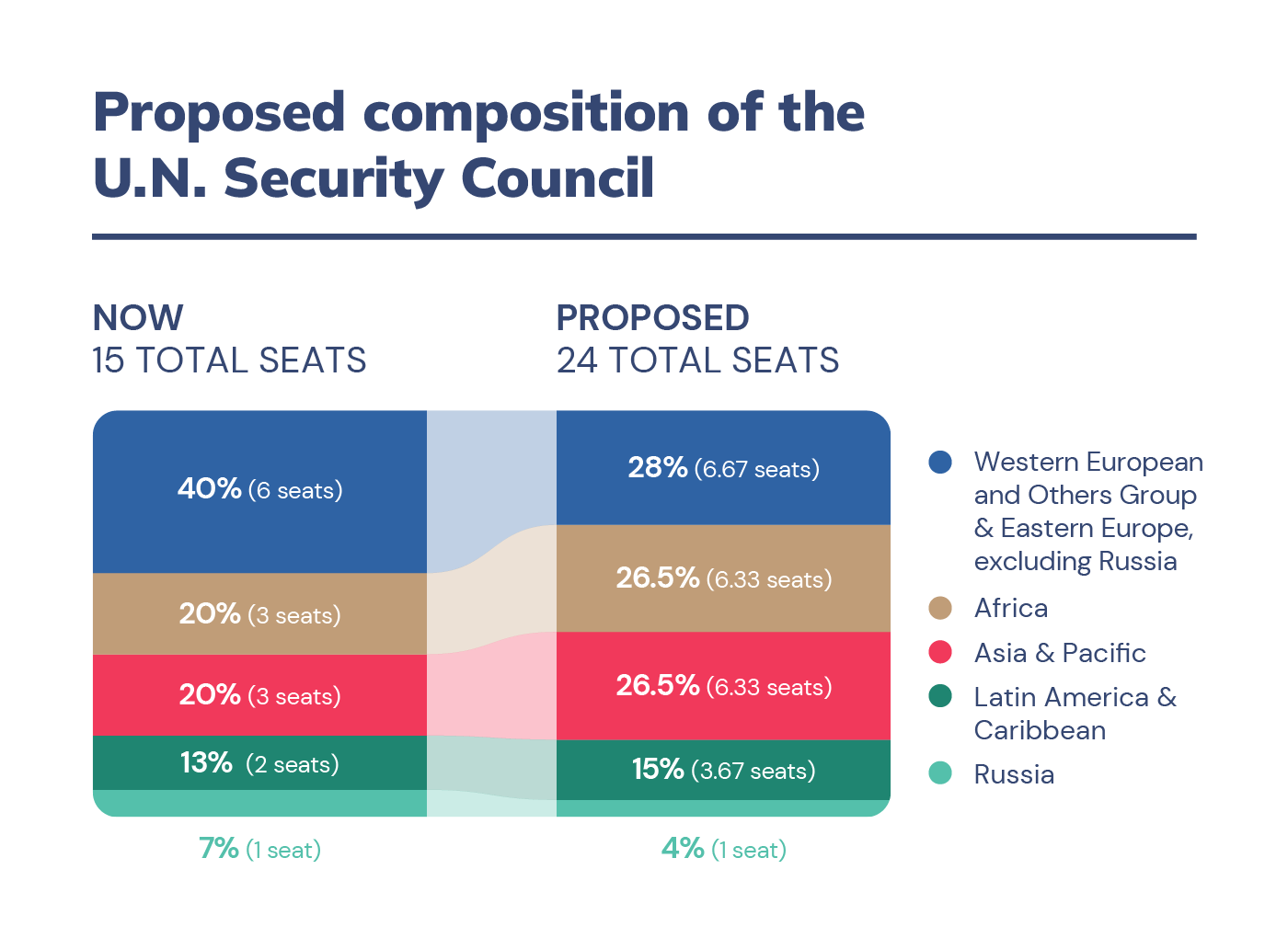

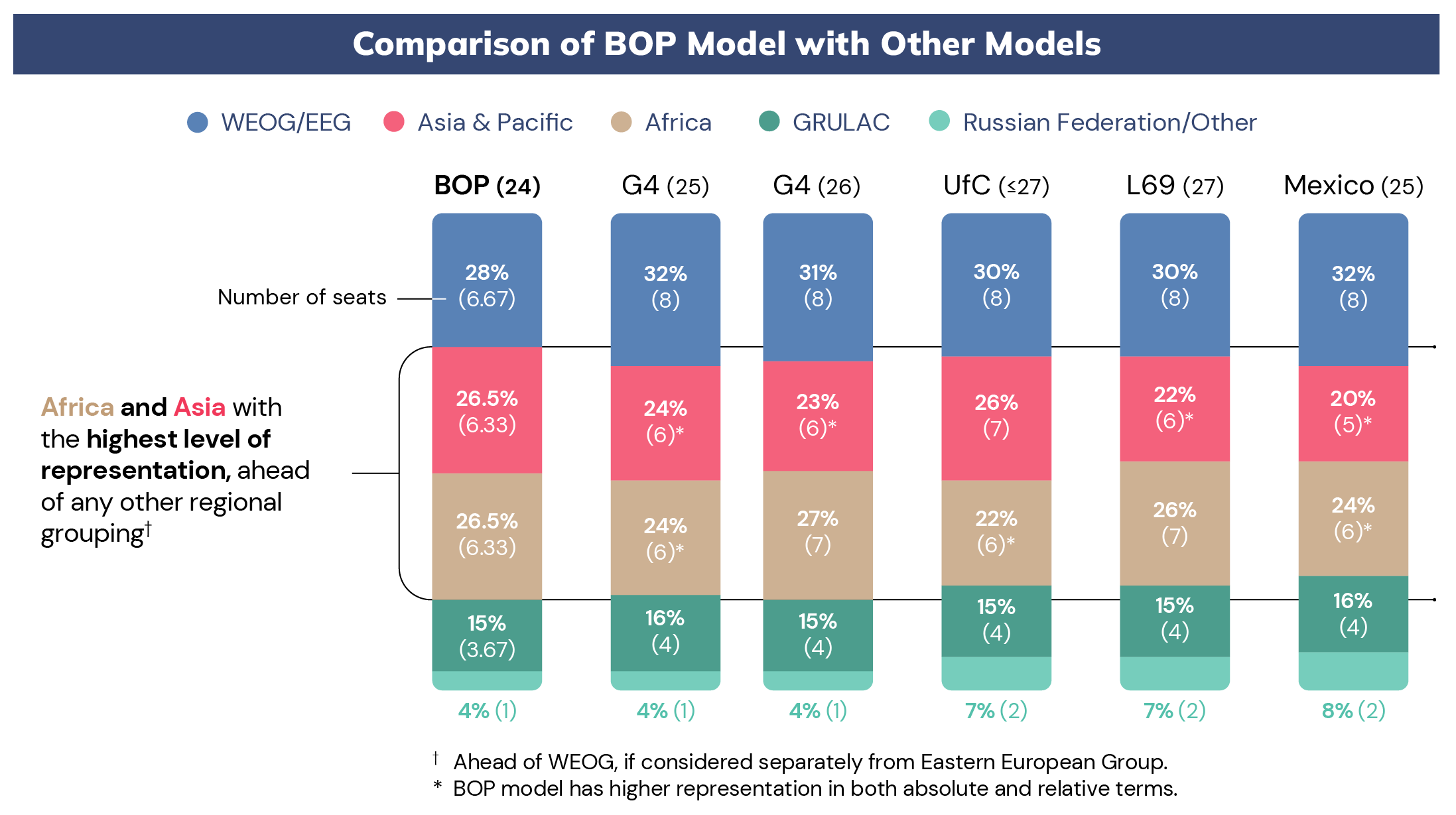

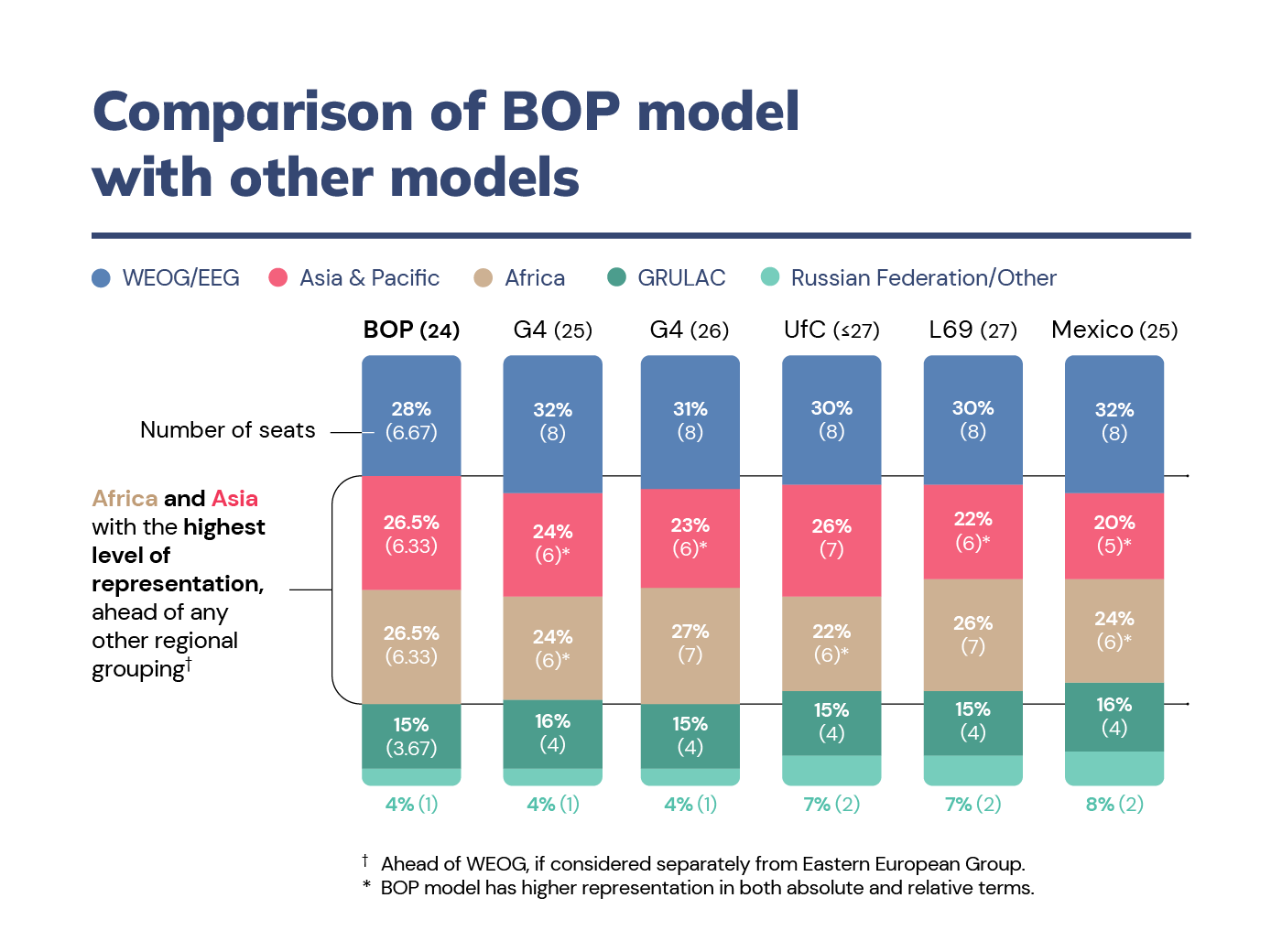

The formula we have developed in Proposal 1 would render Africa and Asia the two most represented regional groupings on the Council, ahead of the Western European and Others Group.1 Our model gives Africa and Asia each more than 26% of the seats on the Security Council. No other existing model offers both Africa and Asia that high a level of representation at the same time. Moreover, unlike other models, the distribution envisaged by the Better Order Project offers Africa and Asia equal representation.

In addition to the proposals outlined below, amendments to the U.N. Charter should explicitly account for the importance of issues of planetary concern, making clear that the remit of the international community’s most inclusive body is no longer limited to issues of international or even global scope.

Proposal 1: Reforming the composition of the U.N. Security Council

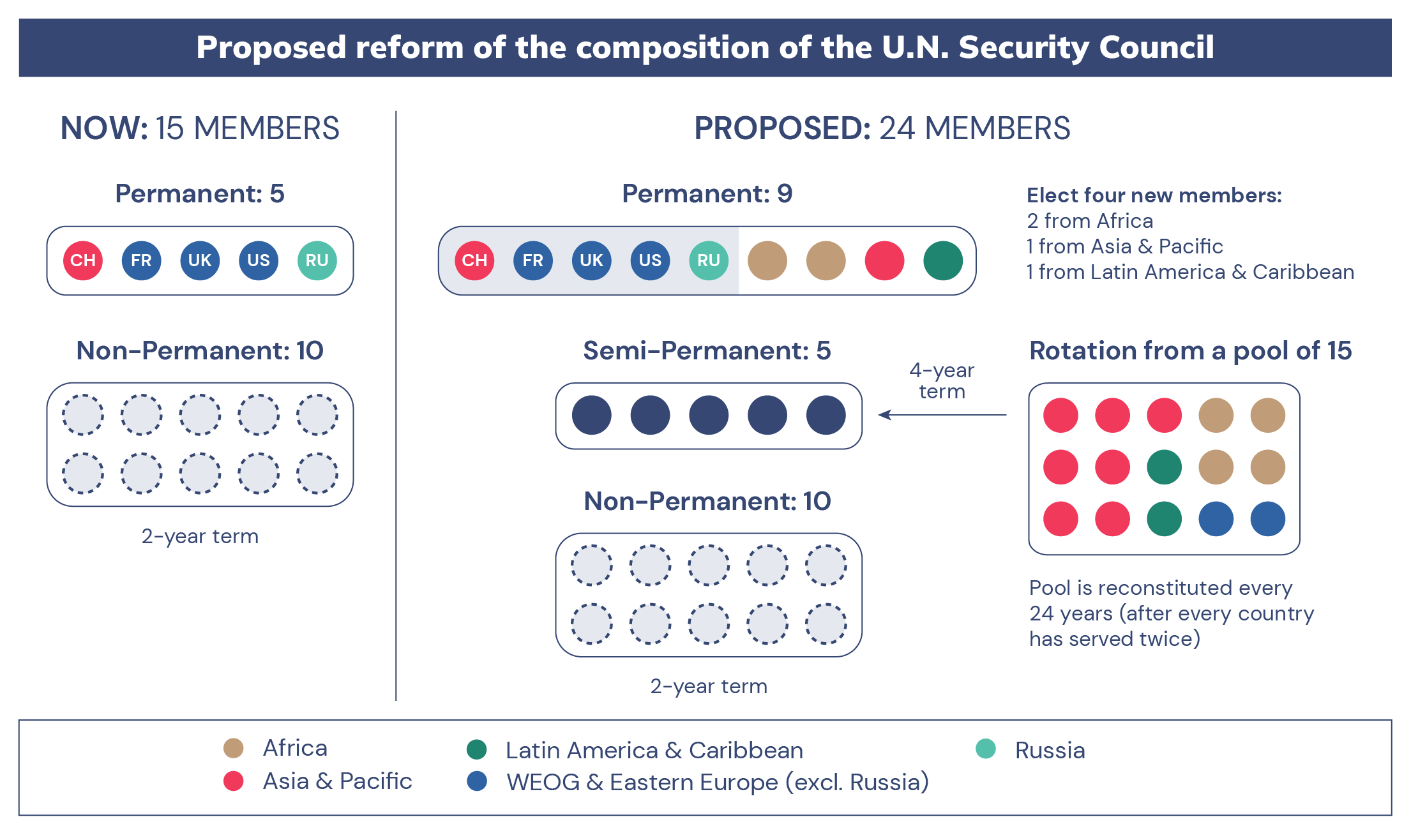

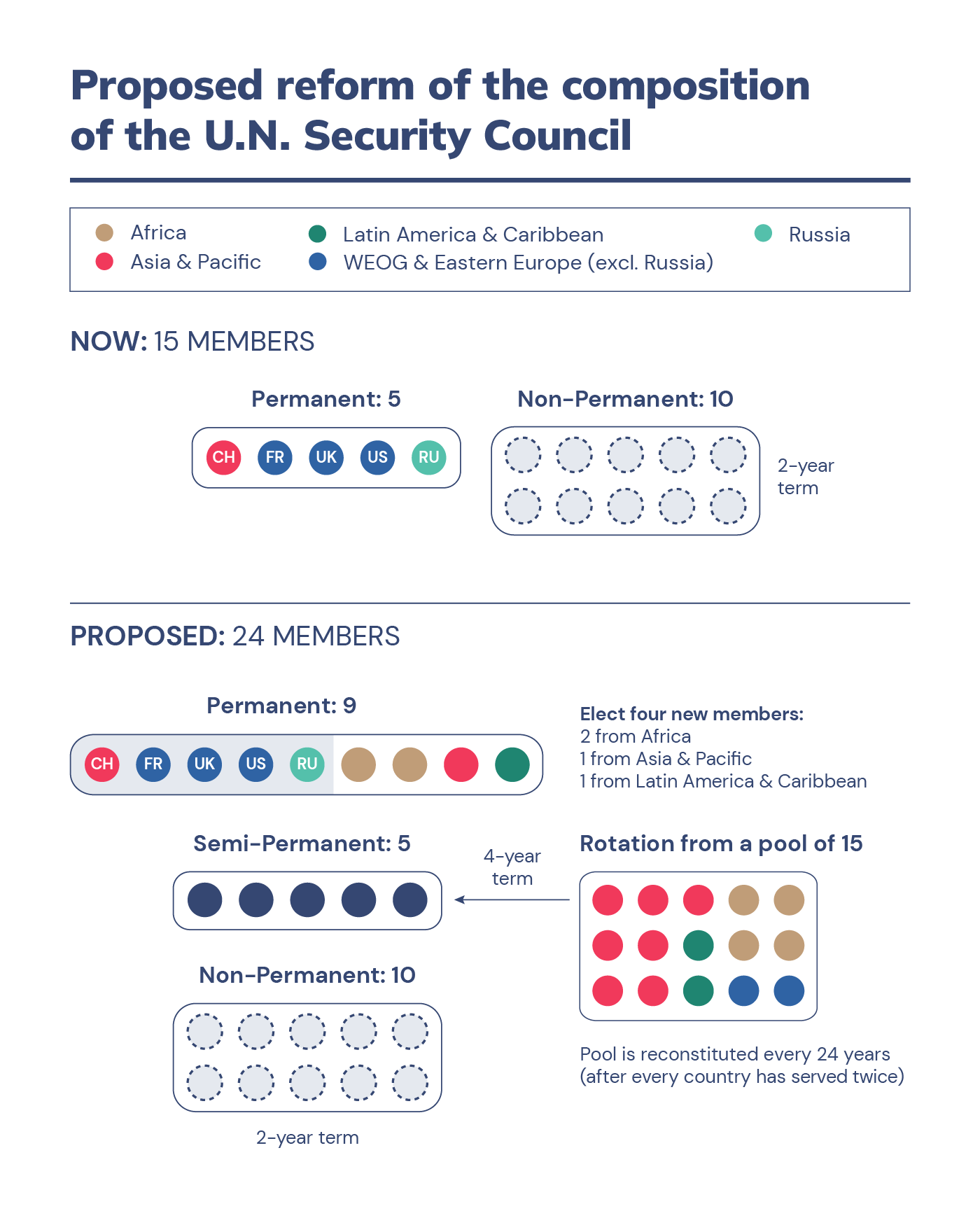

Two specific reforms to the composition of the UNSC should be envisaged. First, given the growth in the number of countries of global influence since 1945, the number of permanent members should be increased. Second, a new semi-permanent category of members should be created to reflect the proliferation of countries of regional (and transregional) influence. The existing category of 10 elected members would remain untouched.

…the purpose of this reform is to create a ‘win-win-win’ formula through which countries of global influence, countries of regional influence, and smaller countries can all improve their positions….

The creation of three categories of states on the Security Council does not signal that multipolarity should be equated with hierarchy. Rather, the purpose of this reform is to create a “win-win-win” formula through which countries of global influence, countries of regional influence, and smaller countries can all improve their positions in the institutional architecture of the international order.

The proposed reforms would result in a total of just 24 seats on the Council — nine permanent, five semi-permanent, and 10 elected members — a manageable number not considerably higher than the current 15 and therefore more likely to win political approval. Of these 24 members, 15 affirmative votes should be required for the adoption of a UNSC resolution — a roughly equivalent share to the current nine out of 15.

- First, four new permanent members should be added to the Security Council: two from Africa, one from Asia and the Pacific, and one from Latin America and the Caribbean. This formula is in line with the Pact for the Future’s recommendation under Action 39(a) to “[r]edress the historical injustice against Africa as a priority and, while treating Africa as a special case, improve the representation of the underrepresented and unrepresented regions and groups”.2

- These new permanent members should be elected by the General Assembly in a vote held two years after this formula is agreed upon, before the completion of the ratification process. Allowing the General Assembly to elect new permanent members strengthens the likelihood that the latter will be chosen for their positive contributions to international peace and security.

- The question of whether new permanent members will be afforded veto powers is addressed in Proposal 2. However, it is worth noting that the process of electing new permanent members in the General Assembly will, on its own, likely reduce veto usage. A country that promises (including through legally binding mechanisms) never to cast a veto — or to resort to one only in exceptional circumstances — will increase its chances of being elected to the Security Council.

- The Group of African States would be able to decide whether it wanted the occupants of its permanent seats to serve on a rotating basis, based on a formula agreed upon among its members.

- The existing P5, in fact, have an interest in growing their own ranks. By agreeing to extend permanent membership on the Council to regions that are currently underrepresented (or not represented at all), the P5 would strengthen the legitimacy of a body in which they would continue to occupy a privileged position.

- An expanded Council may also strengthen the UNSC’s effectiveness, as a permanent member may be more reluctant to bear the political costs of casting a lone negative vote in the face of opposition from an even greater number of permanent and non-permanent members. This would further increase the likelihood that vetoes are cast solely on issues of international peace and security or where a permanent member’s core interests are concerned.

- To avoid setting a potentially destabilizing precedent in which a permanent member is stripped of its seat, the current P5 should retain their status as permanent members of the Security Council.

- Second, once the election of the four new permanent members has been completed, the General Assembly should elect a pool of 15 semi-permanent members, five of which would serve on the Security Council at any given time.3 U.N. members elected to this category are likely to be countries of regional or transregional influence with a demonstrated record of contributing positively to international peace and security. These 15 countries would rotate on and off the Council, automatically serving for four out of every 12 years.

- These 15 countries should be distributed across the U.N.’s regional groupings as follows: seven should be drawn from Asia and the Pacific, four from Africa, two from Latin America and the Caribbean, and two from Eastern Europe and the Western European and Others Group (WEOG) combined. This formula is based on an approximation of the population of these respective U.N. groupings and the number of countries of regional influence each possesses, weighed against the need to improve representation for underrepresented regional groupings. That said, altering it as circumstances demand would not require a Charter amendment.

- After two rotations of 12 years (i.e., 24 years), the pool of semi-permanent members would be subject to review by way of fresh elections in the General Assembly.

- Having an extended turn on the Council once every 12 years — serving a guaranteed eight years out of 24 — would represent a marked improvement for countries of regional influence in comparison with the status quo. It would also offer compensation for those that failed to be elected to a permanent seat. With advanced knowledge of when their tenure will take place, semi-permanent members would be well prepared to make the most of their time on the Council.

- By diversifying the Council’s composition, the creation of the semi-permanent category would offer the 10 elected members of the Council more space to pursue their own agendas. This would be further facilitated thanks to the lengthier, four-year terms that semi-permanent members would serve, which (alongside the election of new permanent members) would ensure that more members than just the P5 possess a high degree of institutional memory and fluency in Council business. Smaller countries would also benefit from no longer needing to compete against 15 influential semi-permanent members (along with the four new permanent members) for an elected seat on the Council.

- Building on the existing practice of ensuring Arab representation, at least one of the Asian and one of the African seats in the semi-permanent pool should be reserved for an Arab country. However, given the number of Arab states that hold significant regional or transregional influence, it is likely that more than two total Arab states will be elected to the semi-permanent pool. If three Arab states are elected to the pool, it would amount to a de facto permanent seat for at least the next quarter-century (albeit without veto privileges), with the possibility of reelection.

- Regional groupings should also consider whether to set aside one of their semi-permanent seats for a Small Island Developing State (SIDS). For example, the Latin American and Caribbean states could set aside one of their two semi-permanent seats for a SIDS country, given that 16 of the 33 member states in this grouping fall under this category. Asia and the Pacific could also set aside one of its semi-permanent seats for this purpose, which would be open to African SIDS as well. Having two SIDS countries as part of the semi-permanent pool would only guarantee SIDS representation on the Council for 8 out of every 12 years; however, it would ensure that a small number of SIDS will develop the strong institutional memory necessary to advance the political agenda of all SIDS more effectively.

To empower the 10 elected members of the Council even further, UNSC members should consider rotating the chairmanship of its subsidiary bodies annually. Such a reform to working methods would not require a Charter amendment. But even without this change, the expansion of the UNSC’s membership would, on its own, offer more opportunities to increase the number of resolutions tabled by members with no veto, as well as to reduce the extent to which established powers wield control over chairmanships and penholderships.

Proposal 2: Limiting the veto

As relations between the great powers have deteriorated over recent years, the Security Council has become increasingly paralyzed. Although the veto’s purpose is to provide great powers with a stake in upholding the international order and to encourage them to remain invested in its institutions, it has also called into question the legitimacy and effectiveness of the primary body tasked with upholding international peace and security. Securing sufficient support from U.N. member states for reforming the Security Council will be very difficult without visibly addressing the question of the veto.

…we propose several limited yet ambitious ways in which veto use could be reduced or restricted.

Any changes to veto privileges should be careful not to encourage further dissociation from multilateralism. Such an outcome may present itself if certain great powers conclude that the U.N. can no longer be trusted as a vehicle for upholding their core interests. Moreover, the employment of a veto can sometimes have positive effects: for example, protecting the sovereignty of smaller states by refusing to authorize a military intervention.

Nonetheless, we propose several limited yet ambitious ways in which veto use could be reduced or restricted. These changes should aim to enhance the body’s efficiency and thus support the interests of the international community, including the interest that the permanent membership has in preserving a functional and legitimate Security Council.

The following recommendations are the product of a compromise between project participants who defended the veto as a necessary prerogative and those who demanded restrictions on its use:

- First, the following restriction on veto privileges should be codified in the U.N. Charter. The strength of the limitation should be dependent on whether new permanent members are given veto privileges:

- In the event that new permanent members agree to forgo their veto privileges voluntarily, this should be done in exchange for the implementation of a “one plus one” mechanism, namely: a P5 member of the Security Council casting a veto will need to secure at least one negative vote from any other member of the Council for the veto to be secure from potential override. If, by contrast, the permanent member is the lone country casting a negative vote, then a two-thirds majority of the General Assembly can overturn the veto through the adoption of a GA resolution. This mechanism will help to level the playing field between the P5 and new permanent members, while also ensuring that new permanent members do not obtain unqualified veto privileges at a later date.

- In the event that new permanent members are given veto privileges, then there is a risk of more veto use and more paralysis on the Council. In this scenario, there will be a need for a stronger veto restriction: one veto plus two other negative votes should be required to insulate the veto from being vulnerable to a review of the General Assembly. Should such a review occur, in this case it should take place by secret ballot. (If discussions in the IGN settle on other accountability mechanisms to constrain new veto-wielding seats, such as subjecting the holders of those seats to fixed terms with the possibility of re-election, then a “one plus one” formula may prove sufficient.)

- In the context of an expanded Security Council membership, a country of global influence should be encouraged — and should easily prove able — to secure the support of just one (or two) of the other 23 Council members for its position. The overturning of a veto would be an exceptional development — one that is likely to occur only when an isolated great power has manifestly failed in its commitment to uphold international peace and security.

- Second, a new prerogative should be extended to the permanent Security Council members, allowing them to vote “no” on a resolution without exercising a veto. This would offer them a new way to respond to domestic political pressures while, at the same time, acting constructively in the face of a pressing need from another U.N. member state to pass a Security Council resolution. It would also raise the political cost of casting a full-blown veto, thereby disincentivizing permanent members from blocking resolutions in instances where the primary considerations are political and do not directly relate to the task of upholding peace.

- Third, the Peacebuilding Commission, which currently focuses on post-conflict peacebuilding and recovery, should be elevated within the U.N. system and be assigned some of the current responsibilities of the Security Council. One way to achieve this might be for the Trusteeship Council to be de facto transformed into a Peacebuilding Council. This development would foster a more democratic and a more efficient international order, while also helping to limit use of the veto to genuine and unquestioned issues of peace and security.

- Cases that do not directly involve a threat to international peace and security should ideally be transferred to the Peacebuilding Commission, allowing the UNSC to tackle a more focused agenda. This should be accomplished by way of a joint decision of the General Assembly and Security Council case by case.

- The General Assembly and Security Council might also consider empowering the Commission to select the cases it chooses to take on independently, including cases taken on at the request of an affected U.N. member state. It should be stipulated that this would not alter the current prerogatives of the Security Council under the U.N. Charter, up to and including the responsibility for authorizing the use of force.

- Topics that an elevated Peacebuilding Commission should address include environmental issues, health issues, education, and infrastructure, all of which fall under a broad sustainable development for peacebuilding definition. Neither peace operations, arms embargoes, sanctions, nor military interventions are pertinent to these issues, making the Security Council a less suitable forum for addressing them. Moreover, the permanent members of the UNSC do not hold special veto privileges on the Commission, and the affected country can be present.

- Resource allocation within the U.N. system should reflect the Commission’s higher caseload, and countries should be reassured that their cases will remain just as “high-profile” on the Commission as they were on the Security Council, given the redistributed workload. One might also consider adopting changes to the Commission’s voting structure, which currently operates on consensus, as it acquires a more robust mandate. If a country that does not pose a manifest threat to international peace and security (as determined in consultation with its immediate neighbors) wishes to remain on the UNSC agenda, it should be required to provide compelling arguments for this choice.

- Fourth, going forward, the process for electing a Secretary-General should begin with the selection of a candidate by the General Assembly, followed by the UNSC’s assent. This could allow for a stronger and more representative Secretary-General to emerge.

- Finally, certain changes to working methods aimed at reducing veto use and strengthening accountability can also be envisaged.

- Building on Liechtenstein’s veto initiative, which allows the General Assembly to convene within 10 working days of a UNSC resolution being vetoed, the GA should proactively make recommendations to UNSC members on how to avoid the disputes and disagreements that led to the casting of a given veto. This would strengthen intra-body dialogue at the U.N. and help ensure that the casting (or threat) of a veto does not entirely shut down debate.

- Relying on legal advice and drafting assistance provided by the Secretariat, a special working group should be established to draft General Assembly resolutions in advance on issues that are frequently subject to UNSC vetoes. This would allow the GA to act swiftly when needed in the context of a veto initiative meeting. The working group should be established — and its members selected — by way of a two-thirds majority vote of the General Assembly.

Proposal 3: Automatic Charter reviews

An amendment to the U.N. Charter should stipulate that a Charter review will be automatically held every 24 years. This would coincide with the conclusion of two cycles of semi-permanent members rotating on and off the Security Council, an appropriate juncture at which the entire package of reforms proposed above can be revisited. Those recommendations listed above that fail to garner the requisite support could be revisited during the next Charter review, by which point the diffusion of power and influence in the international order would have become even more manifest.

Automatic Charter reviews would render the task of Charter reform less politically charged, thereby enhancing both democracy within the U.N. system and the resilience of the organization (and, by extension, the international order) as a whole. Individual member states would be given the right to table amendments for debate, subject to existing adoption and ratification procedures.

- The Better Order Project’s model offers additional benefits for Asia and Africa as well. For example, with 7 semi-permanent seats (2.33 of whom would serve on the Council at any given time), our proposal provides Asia with a greater level of total representation (in relative terms) as the up to four additional non-permanent seats proposed by Uniting for Consensus. As for Africa, the G4 is the only model that may (marginally) provide more representation for Africa than the Better Order Project’s proposal — and this only if Africa is offered two non-permanent seats. But when also factoring in the greater term length of semi-permanent seats, it is more advantageous for Africa to obtain 4 semi-permanent seats (1.33 of whom would serve on the Council at any given time) than to obtain two non-permanent seats. ↩︎

- That said, it is worth noting the ways in which the Better Order Project’s proposal also stands to benefit WEOG and Eastern Europe. For example, although the Mexican model offers these two regional groupings more combined relative representation than any other model, it only sets aside one long-term seat for WEOG, whereas our model sets aside two such seats (represented on the Council for 8 out of every 12 years) and also allows Eastern European countries to compete for these seats. ↩︎

- A variation of this idea was first advanced by Better Order Project participant Kishore Mahbubani. ↩︎